When someone passes away, their financial obligations don’t disappear—and that’s where a tax ID number for an estate becomes critical. If you’re managing an estate, you’ll likely need an Employer Identification Number (EIN), even though no employees are involved. This nine-digit identifier is your estate’s official tax signature with the IRS, and getting it right from the start saves headaches down the road.

Table of Contents

What Is an Estate EIN?

An EIN is a unique nine-digit number assigned by the IRS to identify a business entity for tax purposes. When applied to an estate, it’s essentially a separate tax identity that allows the estate to file its own tax returns and handle financial matters independently from the deceased person’s previous tax situation.

Think of it this way: the deceased had their own Social Security number for tax purposes. The estate is now a separate entity—more like a temporary business—that needs its own identification number. This separation is crucial because an estate generates its own income (interest, dividends, rental income, etc.) and has its own expenses and liabilities.

The estate EIN remains valid for as long as the estate is being settled, which typically ranges from a few months to several years depending on complexity. Once the estate is fully distributed and closed, the EIN is no longer needed.

When You Need an EIN

Not every estate requires an EIN, but most do. Here’s when you’ll definitely need one:

- The estate has income. If the estate earns interest, dividends, rental income, or capital gains, you need an EIN to file Form 1041 (U.S. Income Tax Return for Estates and Trusts).

- The estate has employees. If the estate pays household staff, caregivers, or other workers, an EIN is mandatory.

- The estate operates a business. If the deceased owned a sole proprietorship or other business, the estate needs an EIN to continue operations during settlement.

- You’re opening a bank account for the estate. Most banks require an EIN to open an estate account, even if the estate might not ultimately need to file taxes.

- The estate has significant assets. As a practical matter, estates with more than $600 in gross income typically need an EIN.

There are rare cases where a small estate with minimal income and no business operations might skip the EIN requirement. However, getting one is free and takes minutes, so most executors and administrators get one anyway. It’s like having a legal safety net—better to have it than need it.

How to Apply for an EIN

The application process is straightforward and doesn’t require a lawyer (though complex estates sometimes benefit from professional guidance on broader tax planning strategies).

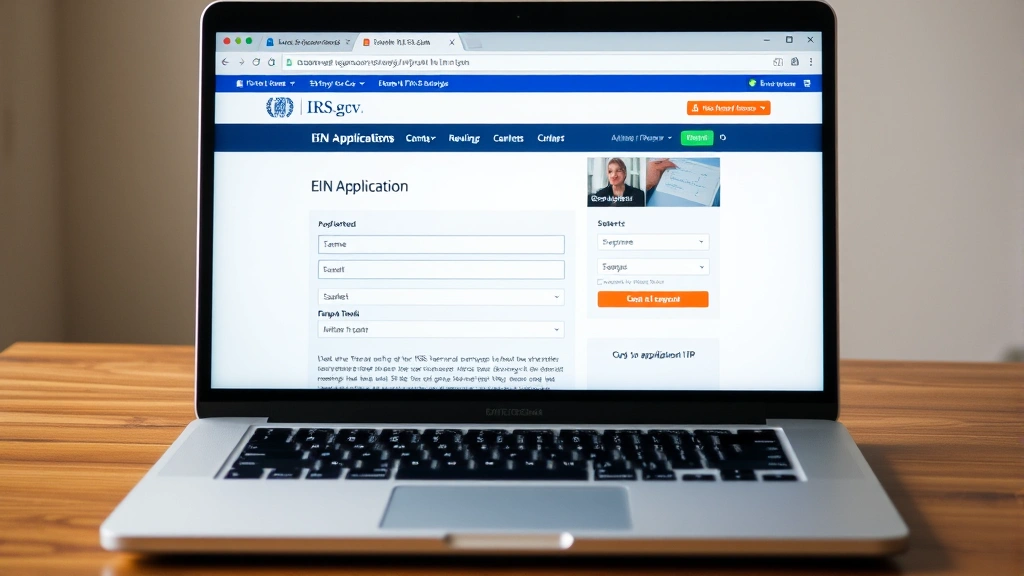

Online Application (Fastest): Go to IRS.gov and use their online EIN application tool. You’ll need:

- The deceased person’s name and Social Security number

- The estate’s legal name and address

- Your name and contact information as the executor or administrator

- Information about the estate’s income sources

The process takes about 15 minutes, and you receive your EIN immediately. This is the method most people use because it’s fast and convenient.

Phone Application: Call the IRS at 1-800-829-4933 (toll-free). You’ll speak with an agent who walks you through the same questions. Processing takes a few minutes, and they’ll provide your EIN verbally on the spot.

Mail Application: Complete Form SS-4 and mail it to the appropriate IRS office for your region. This method takes 4-6 weeks, so it’s not ideal unless you have time to wait.

Fax Application: You can fax Form SS-4 to the IRS (numbers vary by location). Processing typically takes about 4 business days.

Whichever method you choose, have the deceased’s death certificate available. Some applications require it; others don’t, but it’s helpful to have on hand for verification purposes.

Estate Income and Tax Obligations

Here’s where it gets real: once you have an EIN, the estate becomes a separate taxpayer. That means filing taxes, which is one reason understanding tax filing obligations matters.

Estates must file Form 1041 if they have gross income of $600 or more during the tax year. This includes:

- Interest and dividend income

- Rental income from property the estate owns

- Capital gains from selling assets

- Business income if the deceased owned a business

- Distributions from retirement accounts

The estate can deduct legitimate expenses, including:

The estate itself gets a standard deduction ($4,700 for 2023, indexed annually for inflation). Any income above that amount is taxable, though the estate can distribute income to beneficiaries to reduce its own tax burden—a strategy called “income in respect of a decedent” (IRD) planning.

EIN vs. Social Security Number

This is a common source of confusion. The deceased person had a Social Security number (SSN) used during their lifetime. The estate gets a separate EIN.

Why the distinction matters: The SSN is tied to the individual’s personal tax history. Using it for estate accounts or transactions can create confusion with the IRS and complicate record-keeping. The EIN cleanly separates the estate’s finances from the deceased’s personal finances.

When you open a bank account for the estate, use the EIN, not the SSN. When you file the estate’s tax return (Form 1041), you’ll include both the deceased’s SSN (to identify whose estate it is) and the estate’s EIN (to identify the filing entity). The IRS uses both numbers to match everything up correctly.

Some smaller estates might use the SSN for certain purposes, but best practice is to get an EIN and use it consistently. It’s cleaner, more professional, and reduces the risk of IRS mix-ups.

Common Mistakes to Avoid

After years of handling estates, here are the blunders I see most often:

Waiting too long to get an EIN. Some executors delay, thinking they’ll apply once they know the estate will have income. By then, they’ve already opened bank accounts and started transactions under the wrong identifier. Get the EIN early—there’s no downside.

Using the wrong number on documents. Once you have an EIN, use it consistently on all estate accounts, tax forms, and correspondence. Mixing SSN and EIN creates a paper trail that confuses everyone, including the IRS.

Forgetting to report the EIN to beneficiaries. If the estate distributes income to beneficiaries, they need the estate’s EIN for their own tax returns. Provide it proactively to avoid problems later.

Not filing Form 1041 when required. Even if the estate has minimal income, if it crosses the $600 threshold, you must file. Failing to file required tax returns can trigger penalties and interest.

Closing the EIN too early. Estates take time to settle. Don’t close the EIN until all assets are distributed and all tax returns are filed. Prematurely closing it and then discovering you need it again creates headaches.

Timeline and Deadlines

Timing matters in estate administration. Here’s the typical sequence:

Immediately after death: Get the death certificate. Begin the probate process (if required) and notify creditors and beneficiaries. Apply for the EIN within the first few weeks—don’t wait.

First 60-90 days: Open an estate bank account using the EIN. Begin collecting documents related to the deceased’s finances. Notify financial institutions, employers, and government agencies.

First tax year: If the estate has income, file Form 1041 by April 15 of the following year (or October 15 if you file an extension). The estate can elect a fiscal year-end different from the calendar year, which sometimes provides tax advantages.

During settlement: Continue filing Form 1041 each year the estate exists and has income, even if you’re still settling assets.

Final year: File the final Form 1041 and close the estate. Once all beneficiaries have received their distributions and all tax obligations are met, you can request closure of the EIN (though this isn’t strictly necessary).

The timeline varies dramatically based on estate complexity. A simple estate might close in 6-12 months. Complex estates with litigation, business interests, or significant assets can take 2-5 years or longer.

State-Specific Requirements

Federal EIN requirements are uniform, but states have their own rules. For example, some states like Texas have no inheritance tax, while others impose estate taxes or require state-level identification numbers.

A few states require:

- State EIN or tax ID numbers separate from the federal EIN

- State-level estate tax filings (in addition to federal Form 1041)

- State probate court approval for certain transactions

- Notification of state tax authorities within specific timeframes

New York, California, Massachusetts, and several other states have estate or inheritance taxes that require separate filings. If the deceased lived in or owned property in multiple states, you might need multiple state identifications.

Check with your state’s Department of Revenue or Tax Commissioner’s office to understand local requirements. Many states provide guides specifically for executors and administrators. This is also where working with a tax professional on broader tax planning strategies can pay dividends—they know the state-specific traps.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can I use the deceased’s Social Security number instead of getting an EIN?

Technically, the IRS allows using the decedent’s SSN for very small estates with minimal income and no business operations. However, best practice is always to get an EIN. It keeps records cleaner, reduces confusion, and prevents problems down the road. Since it’s free and takes 15 minutes online, there’s no good reason not to get one.

How long does it take to receive an EIN?

If you apply online or by phone, you get the EIN immediately. Mail and fax applications take 4-6 weeks. Online is definitely the way to go unless you have a specific reason to use another method.

Do I need an EIN if the estate has no income?

If the estate truly has zero income and will generate none during settlement, you might technically skip it. But most banks won’t open an estate account without an EIN, so you’ll probably need one anyway. Get it proactively—it costs nothing and prevents headaches.

What if the deceased already had an EIN (from a business)?

The deceased’s business EIN is separate from the estate EIN. If the deceased owned a sole proprietorship, the business assets transfer to the estate, but the estate needs its own EIN to manage those assets and file estate tax returns. The old business EIN is closed.

Can I get an EIN if the estate is still in probate?

Yes, absolutely. You don’t need to wait for probate to conclude. In fact, you should get the EIN early in the process, even if probate is ongoing. The EIN is for the estate entity itself, not dependent on probate status.

Who signs the EIN application?

The executor or administrator (whoever is legally managing the estate) signs the application. You’ll need to provide your name, title, and contact information. The application also requires the deceased person’s name and SSN to identify whose estate it is.

What happens to the EIN after the estate closes?

The EIN remains valid but becomes inactive once the estate is fully settled. You don’t need to formally close it with the IRS, though you can if you want. Most executors just let it become inactive naturally. If the estate reopens for some reason (rare, but it happens), the old EIN can be reactivated.

Final Thoughts

Getting a tax ID number for an estate is one of those administrative tasks that feels bureaucratic and boring—until you skip it and create a mess. The good news? It’s simple, free, and takes minutes. Apply online through IRS.gov, get your number immediately, and move forward with confidence that your estate’s finances are properly identified and tracked.

The EIN is your estate’s official tax identity. Treat it like one. Use it consistently on all accounts and documents, file required tax returns on time, and keep good records. If the estate is complex or involves multiple states, consider working with a tax professional or CPA who specializes in estate administration. The cost of professional guidance is usually far less than the cost of mistakes.

Remember: the deceased’s financial obligations don’t disappear, but with proper planning and the right EIN in place, you can manage them efficiently and legally. That’s what being a good executor or administrator looks like.